I’ve been writing music since I was 14 and I’ve been thinking about copyrighting my music for just as many years. But, I have to confess — I’ve never done it. Every time I made up my mind to apply for a copyright, I’d find myself reading through hours of material. When it came time to do it, I always found a reason not to follow through. Even though I knew I should copyright my songs, I always managed to talk myself out of it. And according to a Tunecore poll from 2011, it looks like I wasn’t alone. 44% of musicians who answered the poll gave their reasons for not copyrighting.

A few thoughts I’ve had while talking myself out of copyrighting music include:

- What’s the point?

- Do my songs really need it? I thought fighting over who wrote what song was only for the rich and famous.

- I heard I could I could mail a copy of my album to myself and that was just as good.

- How do I even do this? I don’t want to fill out tons of confusing legal paperwork.

- It would probably cost my so much money to get all of my stuff copyrighted, I’m not sure it’s worth it.

Fair warning, I’m definitely not a lawyer (no one at AudioTheme is, or they would have written this article). I’ve also never been involved in a legal matter concerning music. However, I thought it would be helpful to share my experiences with other musicians who may have similar thoughts. Hopefully this post will answer some questions. I’ll be focusing strictly on copyrighting within the United States, since that’s where I live. I’d love to learn more about the process in other countries, but that is perhaps something best left for another post.

What’s the point of copyrighting your music?

Did you know that technically, as soon as you create music in a tangible form, it is copyrighted? That means as soon as you write a song down on paper/computer or record it, you own the copyright. Awesome! I can stop writing this post and we don’t have to worry about doing anything else, right? Not quite.

You never actually legally copyright your music. Instead, when you register a copyright with the United States Copyright Office, you’re creating a record of the copyright you already own. Why is this important? Registering a copyright means you have legal documentation that you actually own the song you’ve registered.

This is one thing I found confusing in the past. I found it silly that I needed to create a record that proved my music was copyrighted, since I believed writing down lyrics was already a form of that. That’s when I learned about the perhaps the most important reason to register a copyright.

Prima Facie

Prima facie is Latin for “at first look.” In legal terms it means “legally sufficient to establish a fact or a case unless disproved.” What does that mean? It means that if you are able to provide a registered copyright for a piece of work, it isn’t enough for someone else to prove that they wrote it. They have to be able to disprove that you wrote it. While it may be easy for someone to “pre-date” your music with a falsified copy, it would be much harder to falsely prove that you did not in fact write the music. It’s important to point out that prima facie is only valid if the copyright is registered within five years after creation of the music.

Let’s use an example here and say Tim and Steve are fighting over who owns a piece of music. In a court case where neither one has filed copyright registration, they would each try to prove who wrote the music. However, let’s say Tim has a copyright registered with the Library of Congress. In this case, the burden would be on Steve to prove that Tim did not write the song before Steve can try to prove that he wrote it.

Do my songs really need registered copyrights?

This is totally up to you. On top of the prima facie legal advantage a copyright registration gives you, you receive a few other exclusive rights. Only the author (owner) of a copyright has the right to make or distribute copies of the work. Remember the Metallica v. Napster case? Metallica’s argument was that Napster was completely disregarding copyright law, and didn’t have permission to copy and distribute the band’s music. You also have the exclusive rights to perform the work publicly and prepare derivative works.

As we’ll discuss shortly, copyrighting is not nearly as difficult or expensive as I originally thought. My philosophy here is better safe than sorry.

I thought I could mail an unopened copy of my music to myself. Isn’t that just as good?

Ah, the “poor man’s copyright.” You’ve probably heard of it before. You mail a copy of your music to yourself and never open it. This supposedly creates a copy of your work with a federal date attached, which could be used to prove creation. I first heard about this in college and even then I was skeptical. While this may have been suitable proof of copyright ownership at one time, it is directly mentioned on the US Copyright Office website:

“The practice of sending a copy of your own work to yourself is sometimes called a “poor man’s copyright.” There is no provision in the copyright law regarding any such type of protection, and it is not a substitute for registration.”

If you are concerned enough to mail a copy of your music to yourself, you should probably just register the copyright properly.

How to copyright music

Registering a copyright within the US is easier than I initially thought. Let’s walk through the stages as I legally register the copyright to my record “One More Cup of Coffee”.

- You can register a new account with the the US copyright office by visiting their website. Input your legal name and other contact information to create an online account.

- After you register, you land on a page that will show a record of all your copyrights. It most likely displays zero records if you just registered.

- From the left navigation menu, click “Register a New Claim”

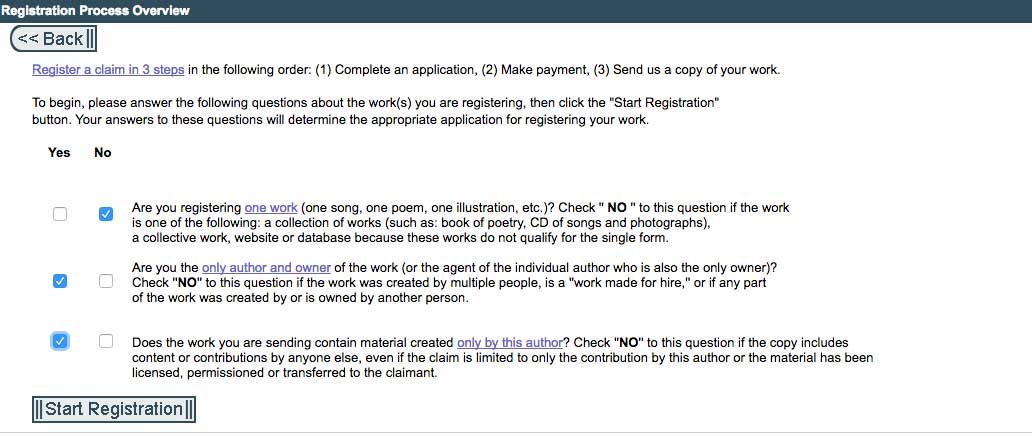

- This brings up a screen with a few questions. First, it asks if you are registering one work (like one song). By clicking “no“, you’re able to register a copyright for an entire record. You can actually register all of your songs as a collection under one copyright registration. This is what makes the process more affordable than I initially thought. The next questions relate to who created the material. Was it just you? Does it contain only content created or licensed by you? In my case, this is all original music, so I’ll check yes on both of those boxes.

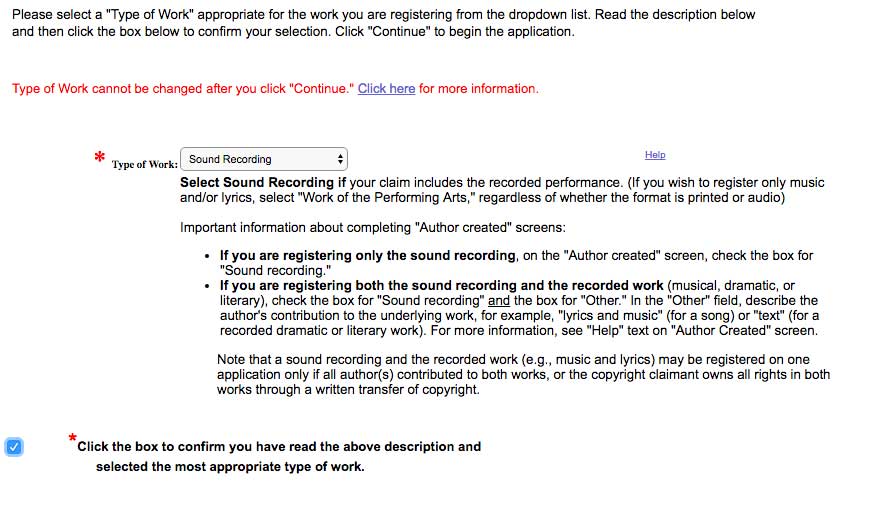

- The next step is selecting type of work from the dropdown menu. Here is another step that may be confusing. Am I registering a sound recording or work of the performing arts? After reading through the site’s help section describing both types, it seems sound recording is the correct type of work. Sound recording allows us to register both the music itself, as well as the performance of it. That’s it for this screen.

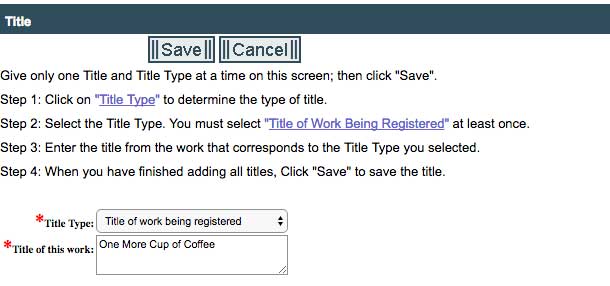

- Next, we click “New” which forwards us to another screen asking for a title type and title. Since this is the first time I’m registering this work, I’ll select “Title of Work Being Registered”. Next, I’ll enter the name of the record, “One More Cup of Coffee” and click save.

A money saving tip here. You can actually lump all of your songs together in one collection together. Say you had 50 songs, you could still register them all under one copyright titled “complete works” or something similar.

- After I enter the title, the next few screens ask some questions. Has the work been published? In my case yes. Year of completion, date of first publication, and nation of first publication are all fields in which I can enter information. I don’t have an ISN or Preregistration number, so I won’t worry about those.

- Next, I’ll add myself as the Author, and verify that I am in fact the author who created the sound recording. As a side note, there is a field for pseudonym here. Let’s say you have a performing name, you want to include it in this box. If your situation is like mine and you have a long first name legally and go by a nickname, you don’t need to use the pseudonym box.

- I’m also the sole claimant, so will fill out the next sections the same way.

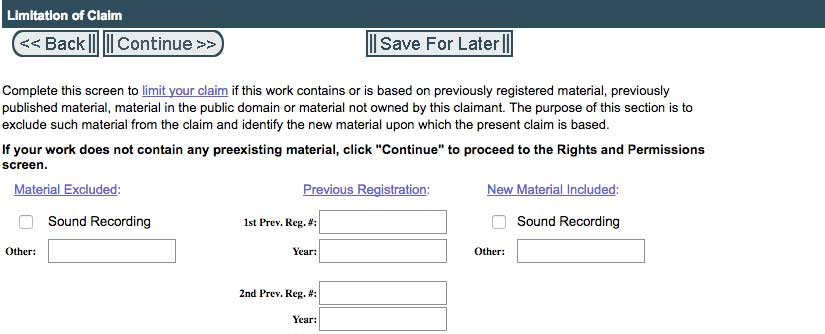

- The next screen covers Limitation of Claim. Since I’ve created everything on the album and it’s not been registered before, I’ll leave this blank and continue.

- The rights and permissions information screen is next and is optional. It gives you a chance to provide contact information for the person who can be contacted for permission of use. I’ll enter my own information. You can add a manager or other point of contact here if you wish.

- The following screen is the correspondent screen. It is required in case the Copyright Office has follow up questions about the request. Again, I’ll use my own information here.

- Next, you’ll be asked to include an address so the office can mail you your certificate.

- You’re able to specify special handling on the next screen if you fulfil special requirements. Since I’m not involved in a legal situation or under deadline, I’ll skip this screen.

- The next screen is the certification, claiming that you’ve added true information and are the exclusive owner of rights.

That’s the end of the paperwork! You can now add your registration to the shopping cart and pay for it.

Total cost? $55.00.

Submitting your music

After you submit the paperwork and pay for your registration, you still need to submit your music. The easiest way to do this is to upload your mp3 files immediately after paying. However, you also have the option to mail a physical copy of the music in.

That’s all there is to it! No lawyers, no confusing paper work, no thousand dollar expenses. You’ve registered your copyright to your album. In a few days you’ll have registered proof of the fact that you created your music.

I also want to point out that the website has great tooltips and help text on how to copyright music. You can actually call in and talk to a live person if you’re struggling with a certain stage of the process. I made a call just to verify this was true.

A few other points

There are some things that registering your copyright will not protect. These include short phrases, general ideas, or chord progressions. In other words, you can’t sue someone who uses a few identical or similar words, or writes a song about a similar general idea. It must be obvious that they’ve stolen your work purposefully. The copyright is also not indefinite. It will extend 70 years beyond your death, but eventually lapses.

That’s it. I almost definitely won’t ever need to sue someone for stealing my music, or ever prove ownership. Those mp3s will probably sit in the copyright office forever without being listened to. But, I now have peace of mind knowing that I am protected if something should happen, and that is well worth the time and money.

I appreciate this. I am a songwriter and Hip Hop Artist. And, I found out that an artist with ATLANTIC RECORDS was stealing my lyrics and/ or changing 1 word from the lyrics of 2 different songs. I noticed that he stolen other artists lyrics because I am on reverbnation.

I can prove that I create the work 1st plus I can prove that he was stealing lyrics from members with a reverberation profile.

I have kept it on my Twitter profile since I found out.

But thanks